Yoi kayōbi o!

^ That’s “happy Tuesday” in Japanese. (virtual 👊 to the person who uses the phrase in a conversation today.)

I recently came across a word that exemplifies why I love Japanese culture.

Tsundoku

It’s having stacks of unread books throughout your house.

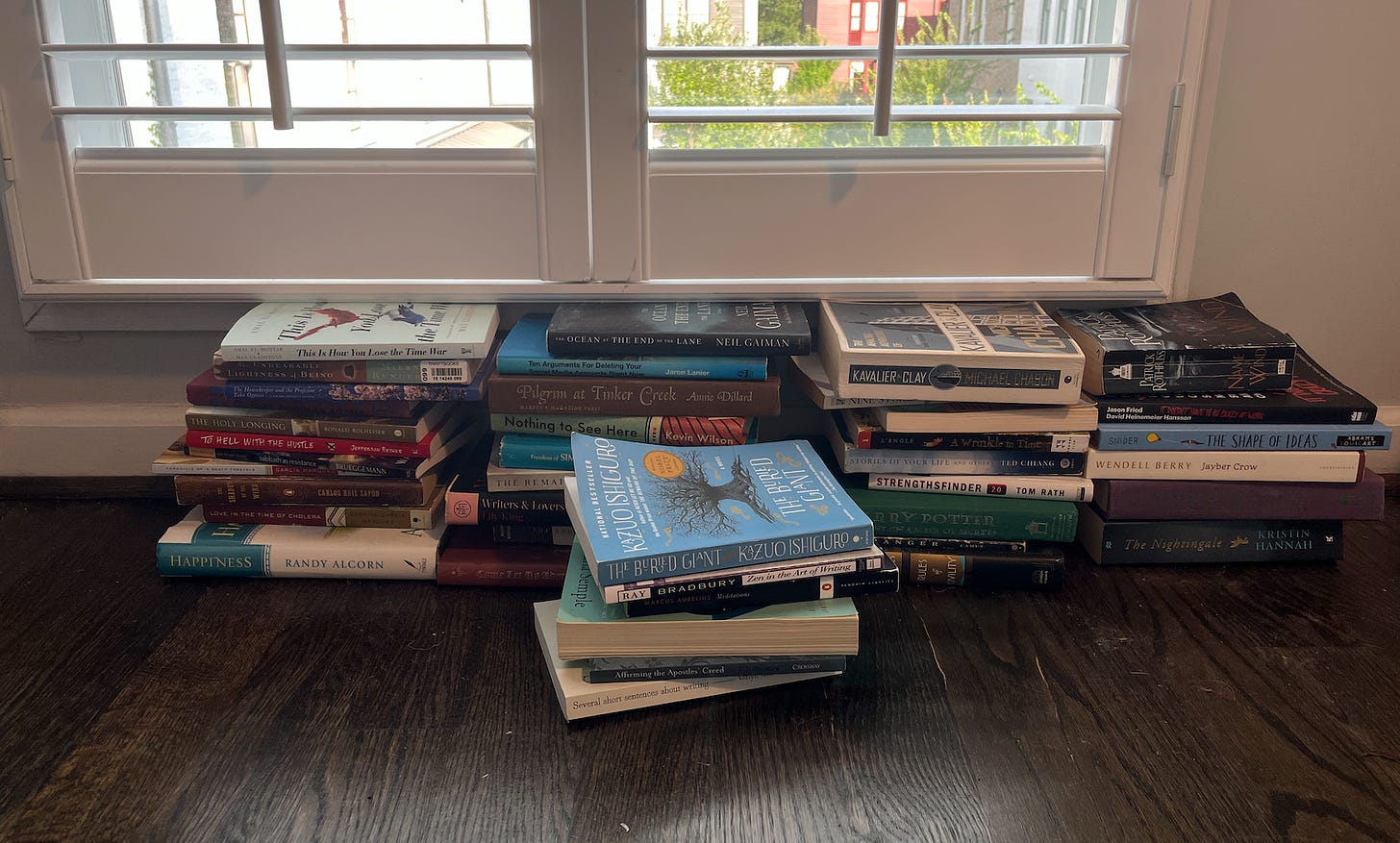

Nightstands are hubs for tsundoku. Here’s a glimpse of my tsundoku.

I’m more guilty of Iejū ni ippai no mizu o nokosu. That’s “leaving cups of water throughout the house.” I’m not forgetful. I’m just using M. Night Shyamalan's strategy of stopping an alien invasion.

OK, that’s enough Japanese words jabbing our flaws.

But if you are struggling to develop healthy habits — like reading books and drinking water — here are two Japanese practices to help you out.

Kaizen

Also known as the one-minute-principle, Kaizen encourages you to commit to an activity for at least one minute, every day at the same time.

Kaizen is an approachable way to continuously improve.

Originating post-WW2 in Japanese businesses, Kaizen became widespread largely thanks to Toyota. (No wonder Toyota has the longest-lasting cars.)

Brian Tracy said,

“The hardest part of any important task is getting started on it in the first place. Once you actually begin work on a valuable task, you seem to be naturally motivated to continue.”

The fear of perfection often prevents you from ever getting started. But one minute can be the momentum you’re looking for.

If you’re struggling to read a book, stop saying, “I’m going to read Moby Dick this weekend.”

Say, “I’m going to read one page at 10pm.”

You’re not going to drink a gallon of water at work.

You’re going to drink a cup of water when you wake up at 7am.

Structure eats willpower for brunch.

Q for you: What’s the one minute you need to put on your calendar today?

Wabi-sabi

No, not the green paste your friends trick you into downing during your sushi debut.

Wabi-sabi means to find the beauty in imperfection.

While the West celebrates perfection and permanence, wabi-sabi recognizes the transient nature of all things. It sees the good in flaws.

Industrialism pushed us toward perfection. But increase in sales of imperfect products like vinyl and printed books prove we have an appetite for lesser quality possessions for the character they offer.

Because imperfections tell stories — like the creaky floors in a Victorian home. Or the jeans you’ve had forever.

It’s common in Japanese culture to mend broken pottery with gold lacquer. This practice is called kintsugi.

Rather than discarding the broken piece or disguising the flaw, the cracks are highlighted as a story to tell. (There’s a sermon in there.)

Q for you: How can you see the good in imperfection today?

PS: Here are two pieces of Japanese content I’ve enjoyed lately:

📚 The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

🎙️ Quality and Wabi-Sabi by Akimbo: a podcast by Seth Godin

PPS: I recently wrote about a home invasion and how some policemen saved the day. I ran into one of the heroes last week!

He encouraged me to say something nice if I posted online because they’re tired — tired of all the crime and the criticism. Like all professions, policemen aren’t perfect. But you can find good ones (pictured below) in the imperfections. Wabi-sabi, friends.